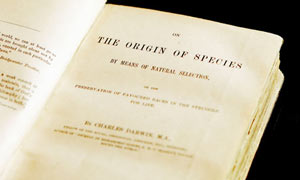

In the opening paragraphs he defines Natural Selection as the "preservation of favorable variations and the rejection of injurious variations" (Page 131). He goes on to explain that this process is as natural and ongoing process.

Over the course of the chapter he brings up case after case of different personal observations and observations of others. As a side thought, its so amazing to see the impact of mass communication in his day. He frequently refers to other scientist who have studied plants and animals and he uses multiple examples across a whole variety of fields to support his thesis (everything from birds and bees to green peas.)

Over the course of the chapter he brings up case after case of different personal observations and observations of others. As a side thought, its so amazing to see the impact of mass communication in his day. He frequently refers to other scientist who have studied plants and animals and he uses multiple examples across a whole variety of fields to support his thesis (everything from birds and bees to green peas.)Anyhow back to the chapter. He brings up a lot of interesting points, such as Sexual Selection or the tendencies to greater reproduction and inter-crossing of individuals or plants. However, the insight that stood out the most to me was that of human interference in this process of natural selection.

As man can produce and certainly has produced a great result by his methodical and unconscious means of selection, what may not nature effect? Man can act only on external and visible characters: nature cares nothing for appearances, except in so far as they may be useful to any being. She can act on every internal organ, on every shade of constitutional difference, on the whole machinery of life. Man selects only for his own good; Nature only for that of the being which she tends. Every selected character is fully exercised by her; and the being is placed under well-suited conditions of life.

Man keeps the natives of many climates in the same country; he seldom exercises each selected character in some peculiar and fitting manner; he feeds a long and a short beaked pigeon on the same food; he does not exercise a long-backed or long-legged quadruped in any peculiar manner; he exposes sheep with long and short wool to the same climate. He does not allow the most vigorous males to struggle for the females. He does not rigidly destroy all inferior animals, but protects during each varying season, as far as lies in his power, all his productions. He often begins his selection by some half-monstrous form; or at least by some modification prominent enough to catch his eye, or to be plainly useful to him.

Under nature, the slightest difference of structure or constitution may well turn the nicely-balanced scale in the struggle for life, and so be preserved.

How fleeting are the wishes and efforts of man! how short his time! and consequently how poor will his products be, compared with those accumulated by nature during whole geological periods. Can we wonder, then, that nature's productions should be far "truer" in character than man's productions; that they should be infinitely better adapted to the most complex conditions of life, and should plainly bear the stamp of far higher workmanship?

(Paragraph breaks added)

What really strikes me in this paragraph is the divinity of nature. Although Darwin in many ways attacks the theory of creation, he is unable to completely avoid the divinity of nature. And although in a sense he turns his piousness to nature in itself, you cannot worship a work of art without eventually coming also unto the artist. And his words are nothing short of compelling "Can we wonder, then, that nature's productions should be far "truer" in character than man's productions; that they should be infinitely better adapted to the most complex conditions of life, and should plainly bear the stamp of far higher workmanship?"

I prose the same question. Does nature in itself not bear the stamp of far higher workmanship?

No comments:

Post a Comment